William Edgar Easton came from five generations of human rights activists. His paternal ancestors had served in the American Revolution and his maternal ancestors served in the Haitian Revolution. He had African, European and Native American (Wampanoag) ancestry. His skin color was light enough to pass as white, yet he always identified as African-American.

Much like Angelina Weld Grimké, Easton had some illustrious ancestors and was brought up partially in Massachusetts.

As previously stated, he was the fifth generation in a line of activists – let’s just check in and see who some of those were:

James Easton (1754-1830)

William Edgar’s great-granduncle [great-grandfather’s brother]. Of Wampanoag and African descent.

He fought in American Revolution, worked as a blacksmith, ran his own foundry for over 20 years, opened an academic and vocational school for African-Americans and seemed to have a hobby of using sit-ins to integrate churches. Seriously, throughout his adult life he and his family tried to integrate the segregated congregations to which they belonged.

It seems nearly all of James’ children took up his activist ways, most prominently…

Hosea Easton (1799-1837) was a minister, abolitionist, author and human rights activist.

Next in line is James’ grandson…

Benjamin F. Roberts (1815-1881) who was a printer, publisher, writer and activist. Is greatest claim to fame is pursuing Roberts v. Boston – he sued the city of Boston because of its “seperate but equal” schooling system. Despite the involvement of lawyer (and soon-to-be senator) Charles Sumner and lawyer Robert Morris, Roberts sadly lost the case. The case would be cited in US Supreme Court’s ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 in which “seperate but equal” was enshrined in law.

Octave Oliviers was an ancestor of Easton’s mother Marie Leggett. I couldn’t find out much about him except he was a general in Haïti’s revolution.

Easton’s mother was born in New Orleans, of Haïtian parents.

There are other family members who contributed much, but it’s time to skip to our playwright, William Edgar Easton, great-grandson of Moses Easton (Revolutionary War vet and brother to James Easton).

His life:

He was born in Boston. He did a BUNCH of stuff in his life. Let’s play a game – What DIDN’T William Edgar Easton Do in Life? Among the following facts, Mr. Easton didn’t do one of them. What was it?

- Attended St. Joseph’s Seminary in Trois-Rivières, Quebec.

- Taught school in Austin, Texas.

- Edited The Texas Blad newspaper (cool name).

- President of the Colored State Press Association

- Chairman of the Travis County (TX) Republican Party

- Assistant Secretary of the Republican (Texas) State Central Committee

- Secretary of the Republican (Texas) State Central Committee

- Storekeeper at the US Customs House in Galveston

- Desk clerk at the San Antonio Police Department

- Accountant

- Tax collector

- Correspondant for the New Age

- Speechwriter for at least two governors of California

- Speaker for the War Department during WW1

- Supervising custodian for all state offices in LA

- Clerk for the California Bureau of Purchases

- Governor of Idaho

If you picked 17, you would be correct. Yep, never governed the Gem State.

The plays:

Haïti sent a delegation to to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (the one that gave us a famous serial killer).

They asked Frederick Douglass to represent Haïti, which is awesome. Douglass had previously been US Minister to Haïti. And an all-around badass.

In 1893, the post-Civil War rights gains for African Americans were being curtailed. Despite being a Haïtian exhibit, the pavilion attracted many African Americans who probably weren’t into the human zoo-like aspects of, say, The Dahomey Village exhibit.

Easton wrote the play Dessalines, a dramatic tale : a single chapter from Haiti’s history for the 1893 Exposition. The play was performed in Chicago, but not exactly at the Haïtian exhibit.

Now we must delve a bit into Haïtian history…

Haïti was a slave colony run raped by the French. The export was sugar cane. Eventually the slaves found a way to rebel and did just that in 1791. Dessalines was one of thousands of soldiers fighting the French. He became a leader, working closely with the famous Haïtian badass Toussaint Louverture. Meanwhile, having its own revolutionary problems, France declared slavery abolished. Then it gets kinda weird. Louverture and Dessalines then joined the French to fight the Spanish and British. Louverture invaded the Spanish side of Hispaniola and freed the slaves there.

But France is tricky and in 1801 Napoleon thought it’d be a grand idea to restore slavery. Louverture was taken prisoner and died in France. Dessalines and his followers defeated the French soldiers and secured Haïtian independence. Oh, and he ordered a massacre of almost all the white people in Haïti (except for the Poles). And he became president and self-proclaimed emperor of Haïti. As such, he reimplemented the plantation ssytem, ostensibly to maintain Haiti’s economy, but the people felt like they had been enslaved again and it wasn’t long before Dessalines was killed, but we’re not quite sure how.

Thus, Dessalines’ legacy is quite mixed. He was a brave patriot and competant leader who led Haïti to victory over the hated French. He also ordered massacres and in a way re-enslaved his people. And proclaimed himself emperor.

This isn’t quite the same guy in the play – let’s take a look!!

Cultural note: in the Haïtian Revolution, the dark-skinned Haitians and the mixed-race Haïtians (mulatres) didn’t get along much.

I’ve noticed this seems to happen when the colonizers create a class that isn’t at the top nor is it at the bottom: they tend to be despised by both sides, warranted or not. A similar thing happened to the mixed-race Indos of Indonesia during their revolution.

So mulatre Flavien is kind of a dick. And Placide is pretty direct about his feelings.

The synopsis:

Flavien being a dick to Placide. Dessalines shows up and takes all the slaves. Mulatre General Rigaud thinks about joining, but remains loyal to France. Dessalines becomes captor to Rigaud’s sister, Clarisse. Dessalines wants to punish the soldiers who tricked Clarisse and were going to abuse her. Clarisse begs him to spare them. Rigaud and Lefebre meet – again about France. Dessalines shows up. They don’t fight. Later Rigaud confronts him about honor. Fight. Clarisse saves everyone. Clarisse prays. Dessalines becomes Catholic.

Not a shabby plot, but the play is WAY better than the above. The strongest part is truly the dialogue. Easton had a way with words…Flavien is all butthurt over Placide’s insult – he complains to the slaves…

Flavien isn’t woke.

You may have noticed that Easton chooses to use faux-Elizabethan English. Actually, he is quite good with it. A modern production could try dropping it and see what happens.

Here’s where Dessalines shows up:

Dessalines does not mess around and Flavien is still a dick. Dessalines expounds upon his theory that white people are pretty cursed. Imagine this playing in a theatre in Chicago in 1893.

He has a point or two or more…

Rigaud: self-aware dickhead. And he was totally a real person. He was a general in the Haïtian Revolution, but it’s hard to be sympathetic when Wikipedia tells you stuff like this:

“André Rigaud was known to have worn a brown-haired wig with straight hair to resemble a white man as closely as possible.”

Rigaud: not woke.

Do we keep the neo-archaicisms????

Oh, Dessalines’ soldiers don’t believe he could ever like the light-skinned Clarisse:

And like every other American representation of Haiti, one must include an obligatory voodoo scene.

But it is the voodoo scene that gives us our most interesting line:

How is this connected to our plot? Clarisse may become a sacrfice…and even the priestess is spooked by her.

Well, Petou brings word of Clarisse’s imprisonment to her brother Rigaud, who then tries to choke him.

And Rigaud tries to act tough.

The plot, as previously stated, wraps up with a fight between Rigaud and Dessalines…

And when Clarisse extols the virtues of Catholicism to Dessalines, who recognizes its truth and then ends in chaste love with Clarisse. None of that actually happened.

In fact, the Catholic conversion scene could easily be deleted – it really does feel shoehorned in.

Besides this, I feel Dessalines is ripe for revival, with modifications.

Production history of the play:

The play was first performed at Freiburg’s Opera House in Chicago, September 1893.

Dessalines was portrayed by Professor Thomas C. Scottron, who had a very interesting family. His family/descendants includes actress Edna Louise Scottron (niece), inventor Samuel Scottron (brother) and singer, actress, activist Lena Horne (grandniece) and screenwriter Jenny Lumet (great-grandniece) and Broadway actor Bobby Canavale (great-great grandnephew – probably the only time I’ll ever use that word).

Clarisse was portrayed by famed actress and activist Henrietta Vinton Davis. Davis also directed the production. Another great link here.

Following this performance, the play was published.

The play was revived at Trinity Congregational Church, Pittsburgh in 1909. This time she directed and played the flower girl and Dominique (one of the Shakespeare-esque buffoon roles).

The other performance of record is at the Fine Arts Theatre in Boston on May 15, 1930.

This version featured Granville Stewart as Dessalines and Avon Long as the voodoo priest [it seems the priestess became a priest for this production].

The play had a reading in Brooklyn in 2014.

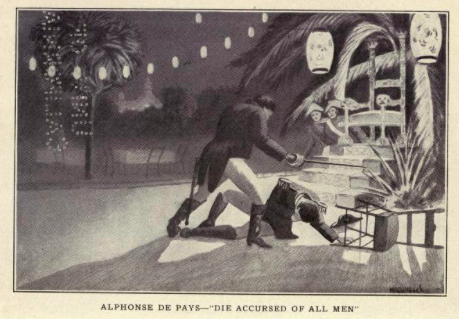

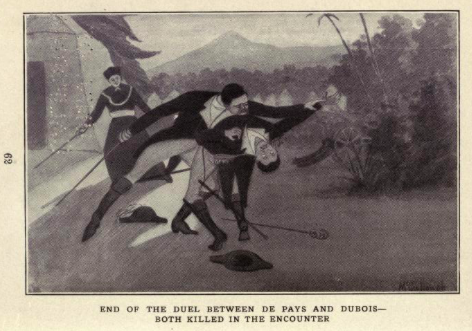

The published volume has several illustrations – the one featuring Dessalines is earlier. These are the others:

Then, after a period of nearly 20 years, Easton published Christophe; a tragedy in prose of imperial Haiti.

The author actually made his own synopsis of the play:

Now it’s not a bad play, but even the synopsis is where things start to falter. There are some things in the synopsis that aren’t even in the play. Not a good sign.

And we must jump back into Haïtian history a bit…

Much like Dessalines, Henri-Christophe had been a general in the Haitian Revolution. Of interest to Americans, he may have served in the American Revolution as a drummer boy with the French at the failed Siege of Savannah in 1778.

He was a harsh general in a harsh time…from Wikipedia:

On 6 April 1805, having gathered all his troops, General Christophe took all male prisoners to the local cemetery and proceeded to slit their throats, among them Presbyter Vásquez and 20 more priests.

He was involved in the conspiracy to kill Dessalines and when he proclaimed himself emperor, he went all in:

“Henry, by the grace of God and constitutional law of the state, King of Haiti, Sovereign of Tortuga, Gonâve, and other adjacent islands, Destroyer of tyranny, Regenerator and Benefactor of the Haitian nation, Creator of her moral, political, and martial institutions, First crowned monarch of the New World, Defender of the faith, Founder of the Royal Military Order of Saint Henry.”

This isn’t quite the Henri-Christophe that appears in the play.

In real-life, Christophe shot himself in the head with a silver bullet [insert werewolf joke here]. In the play he stabs himself with his sword before stabbing someone else.

The play, in my opinion, is quite pedestrian, especially if we compare it to Dessalines. It seems to lack the vigor inherent in plot – it moves forward simply because it has to.

There’s a lot more French used in this play than in Dessalines.

The pseudo-Shakespearean language has been toned down immensely. There’s a part where some Haitians accuse Dessalines of planning to allow white people to live in Haiti:

BURN!!!!!

I found the best bits of dialogue deal with the honorable Dessalines and the traitorous Christophe.

“Puppet of my whims!” <<<< Dessalines pwned Christophe right there.

Snap.

Sadly, Dessalines dies pretty early in the play. And as previously stated, the play plods… a lot. But the book has illustrations. Let’s check out the Classics Illustrated version:

The most interesting thing about the play is the part played by Henrietta Vinton Davis – that of Valerie, who dresses up like a murdering vengeful priest!!!!

If the entire play had been about a woman dressed as a priest killing people, yeah it would be a classic.

It’s still worth a look and maybe other folks will disagree with my assessment.

The play was produced by Miss Davis at the Lenox Casino in New York City with an opening night of March 21, 1912. Fun fact: in 1912 this “casino” was busted for showing stag films.

It is now the location of Masjid Malcolm Shabazz.

Miss Davis played opposite R. Henri Strange as Christophe.

Easton apparently wrote two one-act plays, both with intriguing titles:

Is She a Lady in the Underworld? and Misery in Bohemia.

I can’t find any record of them being performed or published.

There’s also no record of his daughter Athenais becoming a writer as he’d wished for in the introduction to Dessalines.

Thanks for joining us in exploring this playwright’s work and interesting life…

For our other playwrights, please click here.

Join us next week for another thrilling unknown playwright!

Links