This week brings us to the exciting world of Korean theatre. The reason Jo Jung-hwan’s name is written three times in the header is because there are a couple of Romanization systems for Korean. “Jo Jung-hwan” is the one preferred by South Korean government.

“Jo” is the family name and “Jung-hwan” is the given name. For those who are really interested, 趙重桓 are the Chinese characters that make up his name. We’ll get back to Mr. Jo in a bit, but let’s take a brief look at the history of Korean theatre.

Apparently as early as 1,000 BCE Korean shamans were singing and dancing, which brought deities from the heavens to the earth. Shamans (mudang/무당) are still active in Korea, despite the efforts of the South Korean government in the past.

There are some decent Youtube videos covering shamanism and their performances better than I can explain it.

This is looking at the life of a shaman:

This dance started as an exorcism ritual but now is just considered as a cultural performance:

This is a shamanistic ritual for the dead…note the blending of shamanism with traditional instruments…

Much later, masked dances (talchum/탈춤), which had started as something religious, became secularized and a vessel of social satire and comedy. These are called narye (나례) and they look something like this:

Sadly, the masked comic characters only appeared briefly in the above video. For a more ritualized masked dance, there’s this video:

This evolved into an art form called sandaegeuk (산대극)which I think is a bit more well known. This involved the masks, but had a range of stock characters, such a pervy Buddhist monks, greedy government officials and dancing girls. A bit of sandaegeuk from Gyeong-gi Province can be seen below:

Around this time, Korean puppet plays appeared. Their origin is obscure and the haven’t had the staying power of the other forms of traditional Korean drama, but try telling that to the monks and ladies in this play:

There weren’t a whole lot of Youtube videos featuring Korean puppet plays, but that one was awesome. And yes, the lascivious monk trope seems to as old as monkdom itself.

During the Joseon Dynasty two other major forms of performing arts emerged:

Pansori is an intense art that makes opera look like a bunch of Cub Scouts. It started in the 17th Century.

Pansori is storytelling with simply a singer and a drummer. And they go for a long time. Since this was an oral tradition, many stories were added on to. These stories were codified in a way in the 18th century into a pansori cycle. The stories became so long that they lasted 10 hours. In fact, as late as 1969, a famous performance of the renowned Chunhyangga lasted 8 hours. Modern pansori sadly doesn’t go that long.

There aren’t a whole lot of pansori videos on Youtube with English subtitles, but here’s the finale of Shimcheongga with English subtitles:

“I sold my daughter for nothing” has to be one of the more painful lines delivered in theatre.

If you want to see a full, modern pansori, there’s always this:

And for those with a hankering for five hours of nonstop pansori, we got ya covered:

Our final traditional Korean performing art form is changgeuk, which evolved from pansori – it’s like a full-on operetta with pansori models of storytelling.

Here’s a modified version of the same story. Putting it here because it has English subtitles:

All of the above information isn’t intended to be exhaustive – it’s intended as a jumping off point. If you knew nothing about traditional Korean performance art, now you know slightly more than nothing. Hopefully.

And finally, because Korea has a thing for fusion stuff, apparently there was a changgeuk put on in Singapore of The Trojan Women mixed with K-Pop and pansori because Greek and Korean tragedy mix well with a genre that sounds like what would happen if plastic surgery became music.

Supposedly these art forms were all in decline at the end of the 19th Century. Long known as The Hermit Kingdom, the US signed a trade agreement with Korea in 1882. Japan was a bit more direct and simply took the country over.

With various (forced?) cultural exchanges through the elites and mostly filtered from Japanese translations and Lamb’s book, Western drama became known in early 20th Century Korea. Again, this focused on the elites of the day [Huh, theatre really hasn’t changed…snark, snark].

Shakespeare made his first appearence as a mention in a Korean literary magazine in 1906.

With the increasing influence of Japan over its colony, Western drama filtered through. This was modified by Japanese (and then Korean) sensibilities as shinpageuk.

This was a result of several factors, but the forced “modernization” carried out by the Japanese government had some effect.

Here’s a quick chronology of the introduction of Western-style theatre in Korea:

1902:The first Western-style indoor theatre was Heopyeulsa, opened by Korean court officials who had served overseas. Changgeuk evolved here.

1906: Heopyeulsa is closed for violating public morals.

1908: A new theatre is opened on the site by 이인직/Lee In-jik, a court official who had studied in Japan. He introduced a play, The Silver Age, based on a local corruption case. The acting style was still similar to pansori.

1910; 임성구/Im Sung-gu opens a shinpa-style theatre. 혁신단/Hyeok-shindan. Shinpa literally means “new wave” and comes from Japan. That country was inspired by the realism of Western drama and sought to replicate the same.

1911: Im produces a play entitled Undutiful Must be Punished, which was an adaptation of a Japanese shinpa. This was common at the time. Hardly anyone shows up, but Im discovers advertising and his next play is a success.

Much of this information comes from a wonderful paper by Lee Mee-won, which will download if you click here:

1912: The very first published Western-style play script, Three Sick People (병자삼인) is published in installments in the 매일신보Mae-il shin-bo newspaper. That’s our play.

Fortunately the play is a comedy. It was written about and for the emerging “educated” classes that were attending Western-style schools, attending Western-style physicians and slowly adopting Western-style religion.

The plot concerns three men who are outshone by their wives. Jeong Pil-su (정필수) is a guy who attended teachers’ school with his wife, Kim Won-gyeong (이옥자). He failed the teachers’ exam. She passed. She works as a schoolteacher and he works at the same school as what the play calls “servant” (하인) – kinda like a janitor. He resents not having passed the exam and his wife treats him as a servant at home too. He has to cook. OMG.

The second man is Ha Gye-sun (하계순) who is a traditional Korean doctor, but supposedly not a very good one. His wife Gong So-sa (공소사) is a renowned Western-style doctor.

![60090731102030(1)[1]](https://unknownplaywrights.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/6009073110203011.jpg?w=825)

The plot kinda runs like a sitcom. Jeong stays home and must cook all by himself. He flirts with the lady delivering his rice. It seems she feels sorry for him more than anything. His wife Lee sees the rice lady leaving and Jeong catches hell for it. Later Lee tries to teach him Japanese, but he gets so frustrated that he feigns deafness. She makes him go to the doctor (Ha) who gives diagnoses him as deaf. The women kinda know something is up. When Ha’s wife Gong (the better doctor) interrogates her husband about the diagnosis, he pretends to be mute.

Finally there is the school accountant (Park). He is confronted at work one day over an unpaid gisaeng bill by the owner of the house. I’m making a very, very rough equivocation, but gisaeng were kinda like Japanese geisha. Anyways, the owner of the gisaeng house comes to collect last month’s bill. He doesn’t want to pay. She promises him a letter from his favorite gisaeng Mae-hwa in exchange for payment. He pays using school funds. His wife, the principal, confronts him about the missing money. And the letter. Suddenly he goes blind. Doctor Gong threatens to cut out his eyes and everything goes haywire.

The men try to escape/rebel against their Amazonian overlord(esse?)s and reclaim their freedom and manhood. The women chase them. A fight ensues. The women end up in a ditch or in the sewer (if that was a 하수 back then). A policeman shows up and the women accuse the men of doing horrible things [much more horrible than what they actually did]. The policeman can’t believe his luck and threatens to detain the men, but then the women have a change of heart and beg him to release their husbands. The women admonish their husbands to not act stupid again [like that ever works] and everyone holds hands at the end. So it’s better than that one show….

Ironically, the play was NOT performed at the time of publication (which reminds me of another play that got published but is still begging for performance).

What are some things in this play that would recommend it to a revival/adaptation/translation?

- It’s pretty funny. On a “better-than-average-US-sitcom” level. Here Park plays stupid.

[김] 그러면 왜 돈이 부족될 리가 있소.

[KIM] Why are we short on money?

[박] 나는 부족되는 줄을 모르겠는데.

[PARK] I didn’t know we were short.

[김] 그러면 돈하고 회계하고 맞추어보구려.

[KIM] Then you’ll have to balance the accounts.

[박] 무슨 회계하고—

[PARK] What accounting –

[김] 이 회계해 놓은 채부책하고 맞추어 보란 말이예요.

[KIM] I want you to balance this account book

[박] (안경을 쓰고 책을 들여다보며 어름어름하다가) 어디 보이나.

(Park puts on his glasses and looks wide-eyed through the book)

[PARK] Where to look?

[김] 이 합계해 놓은 것 보고, 이 돈을 세어 보란 말이예요, 그래도 몰라.

[KIM] Look at this sum, count this money, I don’t know.

[박] 글세 합계가 어떤 것인지, 돈이 어떤것인지 도무지 모르겠네.

[PARK] I don’t know what ‘sum’ is and I don’t know what ‘money’ is.

(눈을 쓱쓱 씻는다.)

(Rubs his eyes gently)

[김] 나를 속이려고, 나는 벌써 다 알고 있는데, 낫살이나 먹어 가지고 밤낮 계집의 집에만 당기고.

[KIM] I already know about your deception, you’ve been eating at that girl’s house day and night,

[박] 그럴 리가 있나.

[PARK] Is it possible?

Well, dude, if you’ve been doing it, it is entirely possible.

His wife Kim ramps up the pressure:

[김] 그럴 리가 있나, 흥, 그러면 이 편지는 웬 것이야.

[KIM] Is it possible? Hmm, so what’s that letter for?

(하며, 매화의 편지를 내밀어 박원청의 턱밑에 들이댄다.)

(She takes out Mae-hwa’s letter and puts it under Park Won-cheong’s chin)

[박] 응, 무— 무엇이, 무엇인지 도무지 나는 보이지 않는데,

[KIM] Yeah, wha- what, I can’t see what it is.

[김] 아니 보이면 내 읽어 주리까.

[KIM] If you can’t see it, I’ll read it.

(하며 편지를 낭독한다.)

(reads the letter)

[김] 이래도 모른다고 하겠소 그래도 명색이 여학교 교장의 남편이란 사람이 이런 나쁜 짓을 하고 당긴단 말이오.

[KIM] I don’t know but the name of the guy doing this bad thing is the same as the husband of the girls’ high school principal.

If the shoe fits, wear it.

His wife confronts him even more:

[김] 말을 어떻게 알아듣고 그리해. 이 편지가 보이지 아니하느냐 하는 말이요

[KIM] How do you understand language? Do you understand this letter?

(소리를 지른다.)

(shouts)

[박] 도무지 안 보이는데, 어디—

[PARK] I can’t see it all, where —

(하며 눈을 희번덕이고, 손으로 더듬더듬하여 장님모양을 짓는다)

Rolls his eyes, moves his hands around as if he’s blind.

[김] 눈을 뜨고서도 이것을 못 보아요.

[KIM] You can’t see it even with your eyes open.

[박] 응, 눈을 떴어도 희미해서 도무지 보이지를 않네그려. 별안간에 안질이 났나. 원. 조금도 보이질 않는걸.

[PARK] Yeah, it’s blurry when I open my eyes I can’t see at all. Suddenly my eyes are bad. Won. I can’t see a thing.

[김] 그러면 장님이로군.

[KIM] Then you’re blind.

[박] 그렇지 보이지 아니하니까 장님이지.

[PARK] Yes, I appear to be a blind man.

Yes, Mr. Park. It would seem so.

[박] 장님 행세는 어찌하는 것인가.

[PARK] How does a blind man act?

[김] 내 뒤로 와서 어깨나 좀 주물러 주어요.

[KIM] Come behind me and rub my shoulders.

[박] 그건 좀 어렵구려. 명색이 서방님인데 계집의 어깨를 주무르다니, 그건 정말 어려운걸.

[PARK] It’s a bit difficult. Especially for a husband to rub his wife’s shouders. It’s really hard.

[김] 어렵기는 무엇이 어려워. 잔말말고 어서 주물러요. 공연히 분부를 거역하면 서방의 지위까지 파직을 시킬 터이니—

[KIM] What’s the difficulty? Stop complaining and do it. If you disobey the order, you’ll be fired.

(하릴없이 뒤로 돌아와서 어깨를 주무른다. 이때에 하인이 들어오는지라 박원청은 머뭇머뭇한다.)

(He has no choice but to go behind and rub her shoulders. Now the servant is hesitant to enter)

[하인] 지금 여기 공소사께서 오셨는데 교장마님을 잠깐만 조용히 뵈옵겠답니다.

[SERVANT] Kong So-sa is here and she’s waiting quietly to see the principal.

[김] 그러면 이리 들어오시라 하려무나— 그런데 어깨는 왜 안 주무르고 가만히 있어.

[KIM] Then ask her to come in —- Why doesn’t she get her shoulders rubbed?

Ah, the blind masseuse trope…which leads us to reason #2:

2. The women definitely rule over the men.

When Park pretended to go blind, his wife asked for a massage! And then her friend (Kong) showed up…and Kong should get a massage, too!

Quick culture note: the play was written in 1912. In 1913 the Japanese rulers passed a law limiting massage therapy to the blind. That law is still on the books in Korea and emotions run high about it (several blind masseuses killed themselves in protest last year).

These are modern (for then), accomplished women. A school principal, a teacher and a doctor. Remember, this was not far removed from a time when brides’ eyes were glued shut with rice paste at their wedding. The photo in that link is from around 1900. Our play is from 1912.

In Korea, the play is considered feminist, especially given the era.

The whole “men rebelling against women” trope has been used in comedy often. Who remembers Al Bundy’s rebellion against women in Married…with Children?

The women definitely are sharper than the guys here. A production would allow us to see an idea of a “modern” woman in 1912 Korea in a comedic context.

3. Historical significance

As previously stated, this is the first Western-style play published in Korea (though several shinpa were produced prior to this play’s publication). This might be interesting in a Korean theatre festival.

The play feels more modern than you’d imagine a 1912 Korean play. I think this is due to the professions of the characters and the themes.

And now the reason against a modern production:

- The ending. Seriously? These guys lie and act like buffoons simply because their wives are more successful than them. And the one guy is a regular customer at the local gisaeng house. Not much commentary is made on this fact. And at the end all is forgiven. The ending is too easy (even for a comedy).

Despite not being produced back then [or if it was, there is no record] – the play gets produced every now and again…

This is from an adaptation that ran at the Busan Theatre Festival a few years back:

(they translate the title as “Triple Fool” which is plausible, but I prefer “Three Patients”)

Jo Jung-hwan’s life is not well-documented. Some places claim he was born in 1863. Others claim he was born in 1884. He apparently attended a Japanese-language school in Seoul. If we look at his work, he really is known for novels. His first novel was published in 1906. It is also considered one of the first Western-style Korean novels. He remained active for at least ten years.

In addition to the novels, he wrote for a newspaper for 11 years, co-founded the theatre group 문수성/Munsu-seong. He passed away in 1947. Except sometimes his name is given as Jo Il-jae/조일제 and he died in 1944.

I don’t know of any available English version, except what I translated.

I know American playwrights who’ve added lines from another language (usually Spanish) into their play by feeding them into an online translator. For the love of all things holy, don’t ever do this.

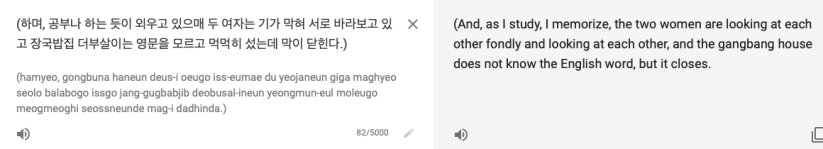

When it comes to Korean to English, Google Translate should be used for entertainment purposes only, as this text from the play illustrates:

Papago is marginally better, yet infinitely more hilarious.

According to the online translation, hedonism was an integral part of Korean theatre in 1912. Who knew?

Here are some links:

This might be the full play from a drama class. The video is “1” and there are a bunch more. All are from the play, but I don’t know if it’s the entire play. This is the first scene where Park flirts with the rice lady: https://tv.kakao.com/channel/3088090/cliplink/386167810

2012 production. Not sure how they got 90 minutes out of this play.

2012 production emphasizing 100th anniversary.

Appears to be a 2014 production.

BEYOND THE LINK DUMP…

Here’s a link to ALL our playwrights.

Something new for the blog…here is a photo dump from a 2015 production in Daehangno [the indie theatre capital of South Korea].

All the photos came from this blog.