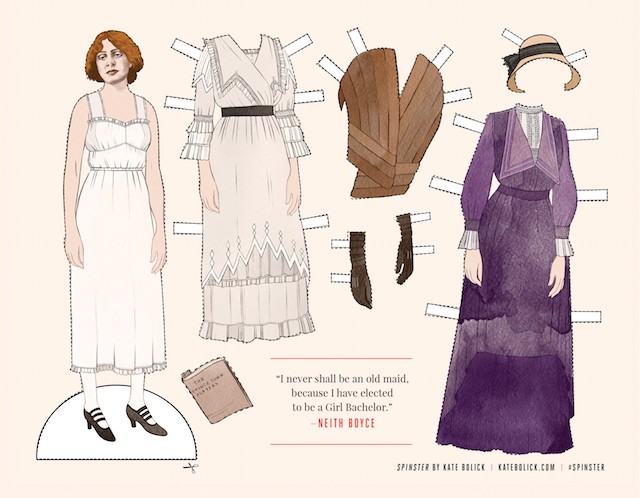

How many Americans born in 1872 were named after Egyptian goddesses? Hint: not many. How many ended up writing plays at the renowned Provincetown Players? Hint: One.

And thus begins the tale of Neith Boyce, feminist, novelist, journalist and…playwright!

Neith Boyce’s life was interesting and tragic, much like her writing.

“She is the terrifying one” is supposedly the original meaning of Nrt, Nit, Net, Neit or Neith (our version) who was an Egyptian godess of hunting and war as well as being a mother goddess. Her cult existed as early as the 1st Dynasty (between 34th and the 30th centuries BC). This made her one of the oldest goddesses of Egypt. As fascinating as all this is, we do need to focus on the writer, but here are some awesome pictures of the goddess Neith:

If you want to learn more about our playwright’s namesake, here is a good place to start.

Neith was born in 1872 as the 4th of five children. This didn’t last long as tragedy hit the family hard: her four siblings died in a diptheria epidemic in 1880. She was mostly raised in Los Angeles.

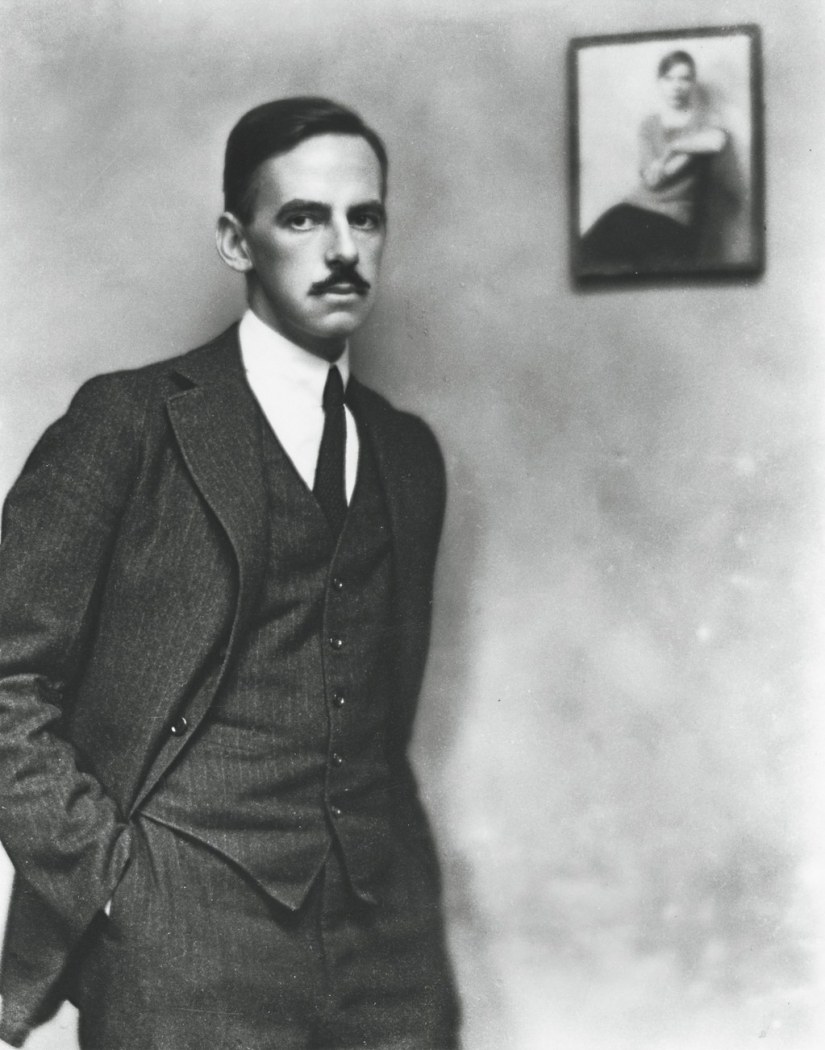

Unusual for the time (but not for Boyce), she pursued a career in journalism and worked in that capacity for The Commercial Advertiser in New York City. She also served as Lincoln Steffens‘ assistant While there she met Hutchins Hapgood, a fellow journalist and future novelist. He came from an interesting family as well. His brother was a writer and editot ended up editing Collier’s Weekly and Harper’s Weekly. His brother eventually ended up as US Minister to Denmark. Oh, and he wrote an article exposing Henry Ford‘s antisemitism.

Side trip warning: Her brother-in-law’s first wife Emilie Bigelow Hapgood ended up producing some interesting theatre. and hung out with Mark Twain.

Meanwhile Norman Hapgood’s second (and much younger) wife ended up being the first English translator of Stanislavsky’s acting tomes.

So even within her married family she had a novelist/journalist husband, editor/journalist/diplomat brotehr-in-law, a sister-in-law who produced plays on Broadway for black people [pretty rare for an upper-class white woman back then] and another sister-in-law who translated Method Acting books. Interesting company she kept.

Other “friends” of the couple I could find include Mabel Dodge Luhan, Djuna Barnes, Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, Gertrude Stein, Carl Van Vechten, John Reed, Margaret Sanger, Susan Glaspell, John Dos Passos, and Mina Loy.

Did you notice playwright Susan Glaspell on that list? Me, too. More on that later.

Marrying in 1899, the couple tried to project an “equal” and open marriage, though it seemed more equal and open for Hutchins than for Neith. From boston.com:

“Boyce’s open marriage, DeBoer-Langworthy believes, enervated more than it energized her — Hapgood exercised its freedoms more assiduously, leaving Boyce to raise their four children –“

Well, that kinda sucks. So apparently she took out her frustration with the pen.

She published several novels (which you should totally check out) before turning to the theatre.

As you may know, Susan Glaspell was a founder of the Provincetown Players. Can you guess who else founded them?

a) Glaspell’s husband Jig Cook.

b) Hutchins Hapgood.

c) Neith Boyce.

d) All of the above.

Yes, these four founded the Provincetown Players, which expanded to include the likes of Edna St. Vincent Malloy and Eugene O’Neill (guess they let anyone in, then).

Meanwhile, the Provincetown Players were (GASP!) amateurs putting on new plays!!!

One well-documented play of Boyce’s that was performed is Constancy, which is about a love affair. Calling it love might be a stretch actually. There are three main things that recommend this play to a modern production.

- The Dialogue

Before introducing Constancy‘s dialogue, let’s take a look at dialogue from the top shows of 1915 for a comparison. This is from the 1912 Shaw play Androcles and the Lion:

LAVINIA. Stuff! Go about your business. (She turns decisively away and sits down with her comrades, leaving him disconcerted).

METELLUS. You didn’t get much out of that. I told you they were brutes.

LENTULUS. Plucky little filly! I suppose she thinks I care. (With an air of indifference he strolls with Metellus to the east side of the square, where they stand watching the return of the Centurion through the western arch with his men, escorting three prisoners: Ferrovius, Androcles, and Spintho. Ferrovius is a powerful, choleric man in the prime of life, with large nostrils, staring eyes, and a thick neck: a man whose sensibilities are keen and violent to the verge of madness. Spintho is a debauchee, the wreck of a good-looking man gone hopelessly to the bad. Androcles is overwhelmed with grief, and is restraining his tears with great difficulty).

THE CENTURION (to Lavinia) Here are some pals for you. This little bit is Ferrovius that you talk so much about. (Ferrovius turns on him threateningly. The Centurion holds up his left forefinger in admonition). Now remember that you’re a Christian, and that you’ve got to return good for evil. (Ferrovius controls himself convulsively; moves away from temptation to the east side near Lentulus; clasps his hands in silent prayer; and throws himself on his knees). That’s the way to manage them, eh! This fine fellow (indicating Androcles, who comes to his left, and makes Lavinia a heartbroken salutation) is a sorcerer. A Greek tailor, he is. A real sorcerer, too: no mistake about it. The tenth marches with a leopard at the head of the column. He made a pet of the leopard; and now he’s crying at being parted from it. (Androcles sniffs lamentably). Ain’t you, old chap? Well, cheer up, we march with a Billy goat (Androcles brightens up) that’s killed two leopards and ate a turkey-cock. You can have him for a pet if you like. (Androcles, quite consoled, goes past the Centurion to Lavinia, and sits down contentedly on the ground on her left). This dirty dog (collaring Spintho) is a real Christian. He mobs the temples, he does (at each accusation he gives the neck of Spintho’s tunic a twist); he goes smashing things mad drunk, he does; he steals the gold vessels, he does; he assaults the priestesses, he does pah! (He flings Spintho into the middle of the group of prisoners). You’re the sort that makes duty a pleasure, you are.

SPINTHO (gasping) That’s it: strangle me. Kick me. Beat me. Revile me. Our Lord was beaten and reviled. That’s my way to heaven. Every martyr goes to heaven, no matter what he’s done. That is so, isn’t it, brother?

CENTURION. Well, if you’re going to heaven, I don’t want to go there. I wouldn’t be seen with you.

LENTULUS. Haw! Good! (Indicating the kneeling Ferrovius). Is this one of the turn-the-other-cheek gentlemen, Centurion?

Now this isn’t a knock on Shaw. His plays tend to be observant and witty and were deservedly popular. But the dialogue is…speechy…

But compare that to the opening lines of Constancy.

REX (Off): Moira.

MOIRA: Rex. There you are. Come ‘round, the door is open.

REX: The door. The door. Oh, very well . . .

(Moira comes back into room, laughing softly. She glances into mirror, touching the circlet around her temples, takes cigarette, lights it, stands leaning against end of couch, looking at Rex. . .

Enter Rex in cape and soft hat which he drops on floor as Moira lazily takes two steps to meet him, with both hands held out.)

MOIRA: Well. Well. Here you are.

REX (Quickly): Yes. I’ve come back.

MOIRA (Lazily): You have come back. How well you’re looking.

REX: I’m not well. I’m confoundedly ill. I’m a wreck.

MOIRA: Oh, no. Come here, let me look at you. (Draws him nearer lamp) Well, you’re a little thinner, but it’s becoming. And you do look tired. But then you’ve had a long journey. Come, sit down and make yourself comfortable. (She drops onto couch. and draws him down.)

The dialogue comes out a bit more natural in this one. Enough that audiences noticed. This can be considered part of the Little Theatre movement, which we’ve covered before.

Here are few other bits:

MOIRA: Oh yes, but letters … There’s a lot one doesn’t say in letters.

REX: Yes, there is. (Gets up, strides to railing, hurls cigarette out, comes back and stands back of couch.) Moira, the last thing on earth I expected was that you should receive me like this.

MOIRA: But why, Rex. How did you expect me to receive you? With a dagger in one hand and a bottle of poison in the other?

REX: Well, I don’t know. But (bitterly) I didn’t expect this.

MOIRA: But what is this?

REX: You know well enough. You treat me as though I were an ordinary acquaintance, just dropped in for a chat.

MOIRA: Oh, no, no. A dear friend, Rex. . . . Always dear to me. (She leans over languidly, drops cigarette in tray, takes gray knitting from desk and knits.)

I like the dagger/poison set up and here we have the conflict. It’s obvious Rex is still madly in love with Moira, but if Moira is interested, she’s being a bit coy. Let’s ramp up that conflict.

REX (Leaning towards her, violently): I don’t believe it. I believe you love some one else. I’ve believed it ever since your telegram to me. Otherwise you couldn’t have behaved so — so —

MOIRA: So well?

REX: If you call it that.

MOIRA: I do, of course. I think I behaved admirably. But you’re wrong about the reason. I don’t love anyone else and I don’t intend to. I’ve done with all that.

REX (Softened, taking her hand.): No, Moira.

MOIRA: Yes, indeed. (Sits up, drawing her hand away, more coolly.) As to my telegram, what else could I do? You had fallen in love with Ellen. You telegraphed me, “Let us part friends”—

REX: But, Moira —

MOIRA (Quickly): Then came your letter telling me that you and Ellen loved one another; that this was the real love at last, that you felt you never had loved me —

REX: Yes, but Moira —

MOIRA: You reminded me how unhappy you and I had been together—how we had quarreled — how we had hurt one another —

REX: Yes, yes, I know, but listen —

MOIRA: And then you begged me to forgive you for leaving me — so — I did forgive you. What else could I do if I couldn’t hold on to you when you loved and wanted to marry another woman.

Playwriting 101 students, pay attention. Rex’ conflict is that he wants love with Moira. Moira is standing in the way of a resolution…

OIRA: You fell in love with another woman, younger, more beautiful —

REX: Moira —

MOIRA: That’s all natural enough. I know what men are. They‘re restless, changeable. You wanted to marry this one — just as —

REX: I didn’t want to marry her.

MOIRA: You didn’t? You wrote me —

REX: Well, perhaps I did, or thought I did, just then… But really it was she that wanted to marry me.

Typical dude right there. Sigh.

REX: When I think what you were last year. What scenes you made if I even looked at another woman. How you threatened to kill yourself when I had just a casual adventure.

MOIRA: Yes — that’s true — I did.

REX: Well, what can I think now except that you have absolutely ceased to love me.

MOIRA: But, my dear Rex, did you want me to go on loving you when you had left me for another woman?

REX: I never left you.

MOIRA: Oh.

“Oh” indeed.

REX: I am going. You never loved me.

MOIRA: Oh, yes I did, Rex. Have you forgotten?

REX: I have forgotten nothing. It is you who have forgotten. It is you who have been unfaithful. I come back to you and you treat me like a stranger. You turn me out. You say you no longer love me. (Regarding her with passionate reproach.) And you told me you had forgiven me.

MOIRA: So I have.

REX: You mean-by ceasing to love me. Do you think anyone wants that sort of forgiveness?

MOIRA: That’s the only sort anyone ever gets.

REX: No. (with emotion) Forgiving means forgetting.

MOIRA (With a wide gesture): Well, I have forgotten – everything.

REX (With a violent movement toward her): You — (Stops and they stand looking at another) And you have called me inconstant. (He backs toward the door with a savage laugh) Constancy!

(Moira stands looking at him, motionless.)

CURTAIN.

Oh, snap, Rex, you just got Rex-jected.

In addition to natural (for 1915) dialogue, the play has wallops of humor, usually delivered in pithily by Moira:

MOIRA: Have a cigarette. I think I’ve some of your kind left. Look over there.

REX: Oh, never mind. (He is gazing intently at her; mutters) I don’t care what kind.

MOIRA: You don’t care. And I’ve kept them all this time. Well then, have one of mine. (She leans to take one from desk, offers it to him, he lights it absently, looking at her steadily as though perplexed.)

REX: Thanks. Moira, I must say you look well.

MOIRA: Yes, I am — very well.

And more:

MOIRA (Counting stitches): One, two, three . . . Well, my dear Rex, you’ve changed a good deal yourself.

REX (Vehemently coming back.): I have not changed.

MOIRA (Dropping her knitting and looking around at him.): Well . . . Really.

REX (Hotly): Of course I know what you mean. Perhaps it’s natural enough for you to think so.

MOIRA (Coolly): Yes, I should think it was.

REX: And yet I did think you were intelligent enough to understand. But even if I had changed as completely as you thought, I still don’t understand why — why you are like this.

don’t understand why — why you are like this.

MOIRA: This again. (Puts up hand to him) My dear Rex, I’m awfully glad to see you again. Do come, sit down and let us talk about everything.

REX (Dolefully): Glad to see me. (He sits at end of sofa) I didn’t think you’d let me in the door.

MOIRA: You didn’t? (Springs up suddenly, drops knitting.) Rex, you didn’t expect to come by the ladder, did you?

REX: Well, no —

MOIRA: I believe you did. This romantic hour, your boat, your whistle — just the same — I know you looked for the ladder.

REX: No, no, I didn’t. I tell you I didn’t think you’d see me at all. But what have you done with it, Moira?

MOIRA: The ladder? (Walks across to table, opens drawer, drags out rope ladder, comes back to couch.) Here it is.

REX: So—you’ve kept it.

MOIRA: Yes — as a remembrance.

REX: Only that?

MOIRA: Absolutely. If you like I’ll give it to you now.

REX: To me.

MOIRA: Yes. You might find use for it some time.

REX: Moira.

MOIRA (Laughing): Well, you know, my dear Rex, you are incurably romantic—and then, you’re still young. As for me, my days of romance are over.

REX: I don’t want that. I want you back as you were before.

MOIRA: You want to make me miserable again. No, Rex.

REX: (Kneels on couch, leans toward her and takes her in his arms. She does not resist.) I can’t believe you mean it. Kiss me. (She kisses him. He draws back suddenly and lets her go.) You do mean it. You don’t care any more. (He drops down on couch. She leans over and caresses his hair.)

MOIRA: Now, Rex, you are just a boy, crying for the moon. As long as you haven’t got it you are dying for it. When you get it you go on to something else. I understand you very well and I think you are the most charming and amusing person I know, and I shall always be really fonder of you than of anyone else.

REX: (Jumping to his feet.) The moon. You are the moon, I suppose, and you are certainly as inconstant. How can you change like this? I come back to you loving you as I always did, the same as ever, and I find you completely changed; your love for me gone as thought it had never been. And you tell me it is no new love that has driven it out. I could understand that, but this… It is true, as Weiniger said, women have no soul, no memory. They are incapable of fidelity.

MOIRA: Fidelity.

REX: Yes, fidelity. Haven’t I been essentially faithful to you. I may have fancies for other women but haven’t I come back to you?

MOIRA (Looking at him with admiration): Oh, Rex, you are perfect; you are a perfect man.

REX: Well, I can say with sincerity that you are a complete woman.

MOIRA: After that I suppose there is no more to say. We have annihilated one another.

And the final bit of interest about Constancy, and what probably made it infnitely funnier to the Provincetown crowd was the fact that: (from

Since the subject of Constancy was a thinly-veiled representation of the end of the love affair between Mabel Dodge and John Reed, which took place only months before, it would have to have been recently written.

Yeah, Boyce based this on real folks she knew. John Reed is the guy who the movie Reds is about. He came from money in Portland, but devoted his life to journalism (he covered both the Mexican and Russian Revolutions), progressive ideals (he put on a benefit at Madison Square Garden for the Paterson Strike and ended up dying in Russia of typhus. Mabel Dodge Luhan

led an interesting, yet troubled life. She was a banking heiress, eloped at 21, a widow at 23, she had affairs with both sexes, used peyote and attempted suicide at least twice. Feel free to learn more about her here, here and here. She did some writing for the Hearst papers, but is more known as a patron of the arts and building a neat house, which was later owned by Dennis Hopper.

The Provincetown Players website gives even more useful, if gossipy information regarding the play and its performance.

Boyce and Dodge had become close friends and confidantes in recent years and, rather than creating a satirical roman-a-clef of Dodge and Reed, as the content of the play is often described to be, Boyce follows the major thrust of most of her writing: capturing “the difficulties of creating new forms of intimacy between middle-class women and men.”(5) Rather than just an “amusing dialogue,”(6) or “spoof,”(7) or “farce,”(8) as it has been described, this play can be seen as the story of a woman who rids herself of her dependency (or in contemporary psychological terms “co-dependency”) on a younger man whose idea of fidelity is that he “would always come back,” even after affairs with other women.(9) She matures while he remains as before and, because he cannot understand her change, believes her to be the one “inconstant.”(10) Sarlos judges that the play is dramatically weak because the female character’s strength “prevents dramatic conflict.”(11) Murphy feels that “its lack of resolution is telling” because these new Modern advocates of free love “had not found a way to resolve their uneasiness around these issues.”

The actual staging of the play is documented, too. Again from the Provincetown Players site:

The famed July 15 performance took place on the oceanside veranda of Boyce and Hapgood’s rented cottage. Kenton reports that the house had “a great living room large enough to hold a few players and a fair audience.” Rehearsals had been held “on the beach and in back yards.”(15) Constancy required a sea set: Boyce transplanted Dodge’s Florence villa where Reed and Dodge had stayed to a house by the sea. The famous silk “ladder” that Reed had climbed up to Dodge’s bedroom from his own was replaced in the play with a rope ladder down to the sea that the female character Moira has symbolically removed, thus requiring the male character Rex to enter through the door. Robert Edmond Jones performed duties the night similar to those he’d become famous for: turning unusual spaces into theatrical settings. He used the wide doors that opened onto the veranda into a kind of proscenium arch, the actors performing just beyond it with the “sea at high tide the backdrop and the sound of its waves was its orchestra, while Long Point Light at the tip of Cape Cod carried the eye ‘beyond.’”(16) Kenton described the setting as “the backdrop of the moving ocean with its anchored ships and twinkling lights.”(17) O’Brien, as Rex, began the play by whistling from down below on the beach and then walking around and up to the veranda for his entrance.(18) Kenton describes the set pieces for the play as “a long low divan heaped with bright pillows,” and “two shaded lamps, one on either side of the doorway” as the lighting.(19) Glaspell wrote that Jones “liked doing it, because we had no lighting equipment, but just put a candle here and a lamp there.”(20) Deutch and Hanau report that “The Hapgood house was crowded for that first performance . . .”(21) Boyce wrote to her father-in-law two days after the performance:

You’ll be amused to hear that I made my first appearance on the stage Thursday night! I have been stirring up the people here to write and act some short plays. We began the season with one of mine. Bobby Jones staged it on our veranda. The colors were orange and yellow against the sea. We gave it at 10 o’clock at night and really it was lovely—the scene, I mean. I have been mightily complimented on my acting!!!(22)

Boyce does not mention Cook in the act of “stirring up” others to write plays. This does not refute Cook’s role, but at the minimum shows a stronger involvement on the part of Boyce that summer than the mythology has ever acknowledged.

Eenemies still gets produced every now and again.

This now brings us to another short play of Boyce’s: the melodramatic The Two Sons.

The plot basically concerns an “artistic” son (Paul) who lives with his mama (Hila) on Cape Cod. Stud-muffin brother/son Karl shows up and puts the moves on Paul’s woman (Stella). This is some ripe melodrama. The most interesting thing here may be some gay subtext.

Mom knows more about Paul’s supposed love life than Paul does.

Quoting from this website:

The earliest documented homosexual use is a 1914 description of a party in Long Beach, California, when some “chickens” were invited to meet some prominent “queers”. It was the most commonly used term (together with fairy) before World War II. It was used mainly by “ordinary” and “straight-acting” gay men in preference to a host of words for effeminate gay men: nellie queens, margeries, fairies, pansies, nancy-boys.

I think given the crowd that Boyce ran in, she probably meant the word queer to have two meanings. And 1915 isn’t too far femoved from 1914, albeit on the opposite coast.

“You’re as handy as a woman” from his own mother!

So many people feel like this. Unusual for a parent to either a) know their child that well b) speak so bluntly.

So Karl and Paul meet towards the end and things get heated and Paul pours out his own feelings and he links his relationship with women to that he has with his mother. Paul is self-aware.

Wait, what??? Paul was the “queer” one. Even his mom said so. That dreamboat of toxic masculinity Karl may have a secret.

So now Paul’s girlfriend (who went sailing with Karl) says that Karl was gay and toold queer stories.

Again, from the Rictor Norton site:

For example, in Mary Pix’s play The Adventures in Madrid, which was performed in 1706, a girl dressed as a boy is pursued by a man named “Gaylove” who calls her his little “Ganymede” and “fairy”.

Also:

Speaking of codes, Gertrude Stein in her story “Miss Furr and Miss Skeene” (published 1922 but written 1908–11) describes a female couple who are more than just merry: “They were guite regularly gay there, Helen Furr and Georgine Skeen, they were regularly gay there where they were gay. To be regularly gay was to do every day the gay thing that they did every day. To be regularly gay was to end every day at the same time after they had been regularly gay.”

And well, it is a melodrama after all.

This play is good for the possibility (not mentioned in the scholarly work I read) that Boyce was trying to write for two audiences. One in the know and the other happily ignorant. This play was published.

The Provincetown Players website mentions:

The third play on the third bill of the Players first New York Season in 1916 was most likely produced as a last minute decision. Mary Heaton Vorse wrote John Reed in Baltimore about the bill and told him: “They’re hurrying on that play of Neith’s The Two Sons for the third bill with only a week of rehearsal.”

A week of rehearsal? Hehehe. Sounds like some theatre companies I could name.

Lucy Huffaker thought Boyce’s play was the “best thing she has done,” but [Louise] Bryant wrote Reed that, in her opinion, the play was a “glaring failure,” claiming the audience was “giggling and toward the end roared with laughter. It was really terrible . . . I’m sorry for Neith, but hope it makes Jig realize things.”(12)

Wow. Sucks for Neith. But we have one more play of hers to go over.

ENEMIES

HE: This is the limit!

SHE: [calmly] What is?

HE: Oh, nothing. [She turns the page, continues reading with interest.] This is an infernal lamp!

SHE: What’s the matter with the lamp?

HE: I’ve asked you a thousand times to have some order in the house, some regularity, some system! The lamps never have oil, the wicks are never cut, the chimneys are always smoked! And yet you wonder that I don’t work more! How can a man work without light?

HE: [irritated] But our time is too valuable for these ever-recurring jobs! Why don’t you train Theresa, as I’ve asked you so often?

SHE: It would take all my time for a thousand years to train Theresa.

HE: Oh, I know! All you want to do is to lie in bed for breakfast, smoke cigarettes, write your high literary stuff, make love to other men, talk cleverly when you go out to dinner and never say a word to me at home! No wonder you have no time to train Theresa!

Uhh, He, is Theresa a dog or a maid?

The story behind this: Hutchins and Neith decided to write a play with husband writing the man’s words and wife writing the woman’s words. So technically Boyce didn’t write that line, but she inspired the guy who did.

Basically it’s an arguing couple. No big deal there. The fact it was written by a real-life arguing couple makes it a bit more interesting.

SHE: You are in a temper again.

HE: Who wouldn’t be, to live with a cold-blooded person that you have to hit with a gridiron to get a rise out of?

SHE: I wish you would read your paper quietly and let me alone.

HE: Why have you lived with me for fifteen years if you want to be let alone?

SHE: [with a sigh] I have always hoped you would settle down.

HE: By settling down you mean cease bothering about household matters, about the children, cease wanting to be with you, cease expecting you to have any interest in me.

HE is trying to be provocative.

SHE: He was a good man…. But to get back to our original quarrel. You’re quite mistaken. I’m more social with you than with anyone else. Hank, for instance, hates to talk–even more than I do. He and I spend hours together looking at the sea–each of us absorbed in our own thoughts–without saying a word. What could be more peaceful than that?

HE: [indignantly] I don’t believe it’s peaceful–but it must be wonderful!

SHE: It is–marvelous. I wish you were more like that. What beautiful evenings we could have together!

HE: [bitterly] Most of our evenings are silent enough–unless we are quarreling!

SHE: Yes, if you’re not talking, it’s because you’re sulking. You are never sweetly silent–never really quiet.

HE: That’s true–with you–I am rarely quiet with you–because you rarely express anything to me. I would be more quiet if you were less so–less expressive if you were more so.

SHE: [pensively] The same old quarrel. Just the same for fifteen years! And all because you are you and I am I! And I suppose it will go on forever–I shall go on being silent, and you–

SHE even has some sort of boyfriend. Told you they argued a lot.

SHE: Do you really think we have nothing in common? We both like Dostoyevsky and prefer Burgundy to champagne.

HE: Our tastes and our vices are remarkably congenial, but our souls do not touch.

SHE: Our souls? Why should they? Every soul is lonely.

SHE has a point.

SHE: Well, then I suppose we may be more congenial–for in spite of what you say, our vices haven’t exactly matched. You’re ahead of me on the drink.

HE: Yes, and you on some other things. But perhaps I can catch up, too–

SHE: Perhaps–if you really give all your time to it, as you did last winter, for instance. But I doubt if I can ever equal your record in potations.

HE: [bitterly] I can never equal your record in the soul’s infidelities.

SHE: Well, do you expect my soul to be faithful when you keep hitting it with a gridiron?

HE: Preachers don’t do the things I do!

SHE: Oh, don’t they?

It goes one and on.

SHE: Oh, very well, if you’re so keen on it. But remember, you suggest it. I never said I wanted to separate from you–if I had, I wouldn’t be here now.

HE: No, because I’ve given all I had to you. I have nourished you with my love. You have harassed and destroyed me. I am no good because of you. You have made me work over you to the degree that I have no real life. You have enslaved me, and your method is cool aloofness. You want to keep on being cruel. You are the devil, who never really meant any harm, but who sneers at desires and never wants to satisfy. Let us separate–you are my only enemy!

SHE: Well, you know we are told to love our enemies.

Ouch.

HE: You have harassed, plagued, maddened, tortured me! Bored me? No, never, you bewitching devil! [Moving toward her.]

SHE: I’ve always adored the poet and mystic in you, though you’ve almost driven me crazy, you Man of God!

HE: I’ve always adored the woman in you, the mysterious, the beckoning and flying, that I cannot possess!

SHE: Can’t you forget God for a while, and come away with me?

HE: Yes, darling; after all, you’re one of God’s creatures!

SHE: Faithful to the end! A truce then, shall it be? [Opening her arms.] An armed truce?

HE: [seizing her] Yes, in a trice! [She laughs.]

CURTAIN

Fight, fight, fight. Make love. This one might be worth performing these days.

This pretty much rounds out our profile of Neith Boyce, a woman for all seasons who wrote a few plays.

On Monday we’ll see a monologue by her for Monologue Monday.

For a list of ALL our playwrights, check here.

Link dump:

Her plays:

Constancy text

Background info

The Two Sons text

Background info

Enemies text

Background info

Winter’s Night background info

Her life:

Boston Globe article

1 thought on “Neith Boyce”